脑深部刺激的机制

摘要

尽管脑深部刺激(deep brain stimulation, DBS)长期和广泛地应用于各种神经性疾病的治疗,但其潜在的机制尚不清楚。越来越多的证据表明,DBS 不仅仅是通过抑制或兴奋基底神经节环路,而是通过多模式的机制在发挥作用。DBS 发挥作用的……并不是一成不变,例如,对震颤改善的效果是即时的,而对肌张力障碍改善的效果则需要几个星期,这提示 DBS 影响的可能是神经网络。既往研究证明用 DBS 治疗疼痛和强迫症是影响了神经纤维的传递而不是灰质。本篇文章的目的是利用临床和实验数据来解释 DBS 发挥效应的各种假说。与一些专家的观点一致的是,我们认为「脑深部刺激」一词需要修改。更准确的术语应是「脑深部神经调节」。

介绍

DBS 是一项很成熟的功能神经外科技术,用于治疗各种神经系统疾病 [1]。1987 年, Benabid 及其同事证实,在帕金森病(Parkinson disease, PD)患者中,DBS 不仅实现了毁损术的有益效果,而且在刺激产生不利影响时,能够实现可调性和可逆性 [2]。自此,该项技术为外科治疗运动障碍疾病、疼痛、癫痫等开辟了新的领域。虽然 DBS 现今已得到广泛应用,但其治疗机制仍不清楚。

DBS 机制的最初观点是经典的「率模型」,该理论认为 PD 运动症状是基底节内神经元放电频率的改变所造成的。结合所观察到地 DBS 临床效果,该模型预测 DBS 是通过抑制过度活动的基底神经节来缓解 PD 运动症状。随后有人提出替代假说,修正了研究人员对 「基底神经节-丘脑-皮层」环路的理解。更好的了解 DBS 的机制将有助于医生采用更精准的手术使患者利益最大化,并减少并发症。

本文将借助临床和研究来探讨 DBS 的机制,并评估各种假说干预的效果。

PD 的经验

PD 是一种神经退行性疾病,病因是黒质致密部(substantia nigra pars compacta, SNc)多巴胺能神经元凋亡。多巴胺的丧失会破坏纹状体环路而导致基底神经节内直、间接通路失衡。 因此,基底神经节输出的靶点内侧苍白球(globus pallidus internus, GPi)和黒质网状部(substantia nigra pars reticulate, SNr)神经元的活动也发生了改变,导致运动障碍和经典的「帕金森病三合一」-运动、僵硬和震颤-以及姿势和步态障碍、认知和情感障碍 [3-5]。由于 DBS 首先应用于 PD 治疗,因此目前对 DBS 机制的了解多数来自 PD 相关的研究。

动物和患者神经元的局部场电位(local field potential, LFP)和动作电位研究发现了 PD 特征性病理放电模式,如「爆发」和异常β-振荡(13-35 Hz)。GPi 和丘脑底核(subthalamic nucleus, STN)[6,7] 神经元的放电频率显著增加,但外侧苍白球(globus pallidus externus, GPe)[7] 的神经元放电频率却降低。GPi、GPe、STN 和 SNr 中的β振荡异常特别突出;此外,在 PD 中,原本相互独立的核团放电极为同步 [5]。研究还发现神经元爆发现象的发生概率和放电频率的增加与 PD 患者症状的严重程度密切相关 [8]。这种模式已经取代了 PD 的病因是单独神经元放电频率改变的传统概念。

在 PD 中这些发现意义深远。了解 PD STN 神经元的放电频率和模式、认识 STN 在基底神经节生理和病理生理学中的关键作用,使得 STN 已成为治疗 PD 最重要的手术靶点 [9, 10]。DBS 可能通过破坏基底神经节异常的同步化来实现其治疗效应,从而使各个核团正常化和恢复「功能」,而不是修复病理性基底神经节系统 [11]。

目前还不清楚 DBS 如何发挥其治疗效果; 然而,通过不断的了解 DBS 机制和 PD 病理生理学的进展,促使研究人员重新评估当前的模型,二者之间形成了相互依赖的关系。如,用β振荡的活动作为生物标志物来设计闭环 DBS 系统 [12]。

其他疾病的经验

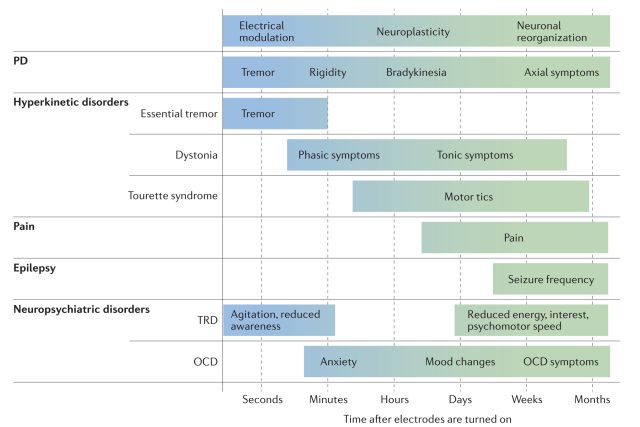

多年来,DBS 适应症的扩展为了解 DBS 的机制提供了重要的依据。在不同的条件下,疾病临床症状改善的时间进程和模式差异很大(图 1):如震颤和僵直通常在给予 DBS 几分钟内就有改善,而运动迟缓可能需要数小时,肌张力障碍或抑郁症的症状改善可能需要数月 [13]。考虑到这些,建议 DBS 治疗应该针对控制特定症状的核团,而不针对某种疾病。这些结果表明 DBS 是通过多种治疗机制,而不仅仅是通过抑制或刺激局部神经元轴突起作用。因此,DBS 疗法是一种多模态神经调节技术,而不是简单地通过刺激局部轴突而发挥作用。

图 1 脑深部刺激效果的时程

有研究表明,肌张力障碍患者症状逐渐改善的机制是由于 DBS 可以改变皮层的可塑性 [13]。 Tisch 等人的研究表明,DBS GPi 使得神经元在几个月内发生重组,使皮层可塑性正常化,症状逐渐改善 [14, 15]。

半个多世纪以来,低频 DBS 被用来治疗难治性疼痛,导水管周围灰质(periventricular grey, PAG)和脑室周围灰质(periventricular grey, PVG)是主要靶点。DBS PAG 提高了内源性阿片样物质的释放,并通过丘脑腹后核向上调节,而 DBS PVG 则是通过增加迷走神经输出来调节自主神经系统的功能 [16, 17]。2013 年,Pereira 等人在 DBS 刺激 PAG 和 PVG 期间给予阿片受体阻滞剂纳洛酮,并同时记录 LFP 确认了该机制 [16]。 这些结果表明,DBS 存在一系列更广泛的治疗机制,可能使术语「刺激」略显不足。

DBS 也常常用来治疗精神疾病。其适应症之一就是难治性强迫症(refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder, OCD)。研究表明,高频刺激(high-frequency stimulation, HFS)可以降低患者的焦虑、强迫思维和行为 [18-21]。与治疗运动障碍或疼痛相比,DBS 治疗精神病的机制是通过靶向刺激特定区域的白质纤维束而不是影响灰质,如内囊前肢的腹尾侧部分 [22]。其作用机制可能类似于电惊厥治疗,激活多个白质纤维束,而不是典型的 DBS 靶向特定的灰质核 [23]。这种机制上的差异可以解释治疗精神疾病为什么需要更高的电压。

DBS 机制:电流假说

经典率模型

最初关于 DBS 机制的经典的率模型被认为是「抑制假说」,该假说认为基底神经节 STN 或 GPi 中过度激活的神经元被 DBS 阻断。该模型假设 PD 的多巴胺剥夺导致 STN 和 GPi 的放电频率升高,进而导致丘脑放电频率降低和运动障碍。这个观点与 DBS 临床观察的结果一致,DBS 起到的效果类似于解剖损毁和生理失活(例如,GABA 激动剂)[24]。虽然研究支持该模型,但这一模型的研究设计存在缺陷,其没有解释刺激物本身 [25-27],因此该假说的发展受到阻碍。当使用新的算法来剔除刺激物本身时,急性 DBS 显示 STN 神经元的活性增加,终止刺激后却立即急剧下降,显然这与抑制假说相反 [28]。

随着思想的不断发展现今提出了一些有争议的假说。这些假说试图解释 DBS 时,神经元到底是被刺激还是被抑制,神经元的哪些部分被调节,传入或传出的轴突是否被刺激,DBS 的作用是局部的还是全身的,神经元或神经胶质细胞是否受影响等。我们将于下文探讨一些相关的假说。

局部或系统效应

早期研究认为主要是植入电极局部的神经元兴奋性与 DBS 的治疗效果直接相关 [29]。 然而,对 DBS 下游核团效果的进一步研究证实了一种更系统的机制,包括激活轴突的传入和传出 [30-32]。在啮齿动物和人的研究中,均观察到下游结构中有神经递质释放的增加 [33-36]。

率模型之外的模型

人和灵长类 PD 模型显示,GPe 和丘脑腹外侧核的放电频率下降,STN 和 GPi 的放电频率增加。然而,在肌张力障碍或运动障碍的病理生理学过程中,多个结果与此相矛盾。1999 年,Jerrold 及其同事发现肌张力障碍患者的 GPe 和 GPi 的放电频率均降低,是不规则的模式,此发现提出了基底神经节的另外一个模型 [37]。

干扰理论。Benabid 及其同事首先描述了干扰的概念 [38]。作者假设通过 DBS 刺激传出纤维的轴突,对轴突施加了时间锁定的高频规则模式,DBS 脉冲之间的短暂间隔会阻止神经元恢复其自发放电活动,包括 PD 患者的病理放电模式。根据这个假说,DBS 不会减少神经元的放电,而是通对病理网络活动的调节引起网络范围的变化。

爆发理论。PD 患者 GPi 神经元的活动不规则,HFS 通过校正病理性爆发振荡模式而发挥作用。在计算模拟实验中,Rubin 和 Terman 发现 DBS STN 后,GPi 调节的放电使丘脑放电正常化 [39]。130 Hz/s 的电脉冲与基底神经节-丘脑-皮层系统的平均生理振荡频率共振,因此在说明高频 DBS 治疗 PD 效果的同时,也解释了低频 DBS 的不良反应 [40, 41]。

破坏病理振荡。通常认为功能神经网络中检测到的振荡是促进空间上不同神经元集群之间的动态交流和可塑性。皮层、基底神经节、丘脑和小脑之间感觉运动环路中的病理性β振荡活动促进 PD 运动症状发生,因为正常的β振荡有助于维持「现状」(停止)行为。因此,异常的β振荡可能会引起运动不能或运动迟缓,DBS 会破坏并抑制β振荡,以减少运动迟缓和僵直 [42-49]。该现象在 Little 等人 8 例患者的验证研究中得到直接证明 [12]。在这些个体中,与传统的连续或随机刺激模式相反,当 STN 刺激只针对病理β-振荡时,患者的症状改善了 50%。然而,考虑到自然β振荡的波动与运动相关,仍然有待观察闭环研究是否能提供类似的证据 [50]。

从基底神经节到皮层

最近的研究表明,急性 DBS 通过减少β振荡与宽频之间的过度耦合从而对皮层有显著影响 [13]。因此,尽管 DBS 电流刺激部位在基底神经节,但神经调节作用的机制至少影响到了皮层。这种现象尤其与肌张力障碍相关,其中皮层可塑性的改变被认为是 DBS 治疗效果的基础 [14]。

结论

自从 Alim Louis Benabid 首次应用 DBS 以来,很多人一直在努力解开其基本机制。探索 DBS 机制的难点在于了解脑生理学和病理生理学。实验和假说是基于当前生理模型的准确所建立起来的,如果当前结果不符合这些模型,那脑生理学、病理生理学和 DBS 机制的概念必须重新评估。尽管实验技术已经大大扩展了我们的知识,采用一些修正和改善治疗方法的新技术,但是 DBS 如何发挥其作用仍然是未知数。

现在的研究证实 DBS 不仅通过局部兴奋和抑制机制,而且通过多种局部和远程因素来调控。不同症状随时间变化对 DBS 的特定变化反应了这种复杂性(图 1)。通过以上结果,我们认为 DBS 的机制是多模式的,包括即刻神经调节作用、突触可塑性和长期神经元重组。鉴于这种观点的转变,我们提出将术语从「脑深部刺激」转变为「脑深部神经调节」,以更准确地反映当前证据。

参考文献

1. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. NICE https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg19 (2003).

2. Benabid, A. L., Pollak, P., Louveau, A., Henry, S. & de Rougemont, J. Combined (thalamotomy and stimulation) stereotactic surgery of the VIM thalamic nucleus for bilateral Parkinson disease. Appl. Neurophysiol. 50, 344–346 (1987).

3. Pollack, P., Gaio, J. M. & Perret, J. Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonian syndromes. Rev. Prat. 39, 647–651 (in French) (1989).

4. Albin, R. L., Young, A. B. & Penney, J. B. The functional anatomy of basal ganglia disorders. Trends Neurosci. 12, 366–375 (1989).

5. Wichmann, T., DeLong, M. R., Guridi, J. & Obeso, J. A. Milestones in research on the pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 26, 1032–1041 (2011).

6. Magill, P. J., Bolam, J. P. & Bevan, M. D. Dopamine regulates the impact of the cerebral cortex on the subthalamic nucleus–globus pallidus network. Neuroscience 106, 313–330 (2001).

7. Soares, J. et al. Role of external pallidal segment in primate parkinsonism: comparison of the effects of 1‑methyl‑4‑phenyl‑1,2,3,6‑tetrahydropyridine‑induced parkinsonism and lesions of the external pallidal segment. J. Neurosci. 24, 6417–6426 (2004).

8. Sharott, A. et al. Activity parameters of subthalamic nucleus neurons selectively predict motor symptom severity in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci. 34, 6273–6285 (2014).

9. DeLong, M. & Wichmann, T. Deep brain stimulation for movement and other neurologic disorders. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1265, 1–8 (2012).

10. Deffains, M. et al. Subthalamic, not striatal, activity correlates with basal ganglia downstream activity in normal and parkinsonian monkeys. eLife 5, 4854 (2016).

11. Wichmann, T. & DeLong, M. R. Deep brain stimulation for movement disorders of basal ganglia origin: restoring function or functionality? Neurotherapeutics 13, 264–283 (2016).

12. Little, S. et al. Adaptive deep brain stimulation in advanced Parkinson disease. Ann. Neurol. 74, 449–457 (2013).

13. de Hemptinne, C. et al. Therapeutic deep brain stimulation reduces cortical phase–amplitude coupling in Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 779–786 (2015).

14. Tisch, S. et al. Pallidal stimulation modifies after‑effects of paired associative stimulation on motor cortex excitability in primary generalised dystonia. Exp. Neurol. 206, 80–85 (2007).

15. Krauss, J. K., Yianni, J., Loher, T. J. & Aziz, T. Z. Deep brain stimulation for dystonia. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 21, 18 (2004).

16. Pereira, E. A. et al. Elevated gamma band power in humans receiving naloxone suggests dorsal periaqueductal and periventricular gray deep brain stimulation produced analgesia is opioid mediated. Exp. Neurol. 239, 248–255 (2013).

17. Knyazev, G. G. EEG delta oscillations as a correlate of basic homeostatic and motivational processes. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 36, 677–695 (2012).

18. Nuttin, B., Cosyns, P., Demeulemeester, H., Gybels, J. & Meyerson, B. Electrical stimulation in anterior limbs of internal capsules in patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Lancet 354, 1526 (1999).

19. Abelson, J. L. et al. Deep brain stimulation for refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 57, 510–516 (2005).

20. Anderson, D. & Ahmed, A. Treatment of patients with intractable obsessive–compulsive disorder with anterior capsular stimulation. J. Neurosurg. 98, 1104–1108 (2003).

21. Aouizerate, B. et al. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral caudate nucleus in the treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder and major depression. J. Neurosurg. 101, 682–686 (2004).

22. Huff, W. et al. Unilateral deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens in patients with treatment‑resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder: outcomes after one year. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 112, 137–143 (2010).

23. Lavano, A. et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment‑resistant depression: review of the literature. Brain Disord. Ther. 4, 168 (2015).

24. Pahapill, P. A. et al. Tremor arrest with thalamic microinjections of muscimol in patients with essential tremor. Ann. Neurol. 46, 249–252 (2001).

25. Benazzouz, A. et al. Effect of high‑frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus on the neuronal activities of the substantia nigra pars reticulata and ventrolateral nucleus of the thalamus in the rat. Neuroscience 99, 289–295 (2000).

26. Dostrovsky, J. O. et al. Microstimulation‑induced inhibition of neuronal firing in human globus pallidus. J. Neurophysiol. 84, 570–574 (2000).

27. Montgomery, E. B. Jr. Effect of subthalamic nucleus stimulation patterns on motor performance in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 11, 167–171 (2005).

28. Montgomery, E. B. Jr & Gale, J. T. Mechanisms of action of deep brain stimulation (DBS). Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 32, 388–407 (2008).

29. Montgomery, E. B. Jr & Gale, J. T. Mechanisms of action of deep brain stimulation (DBS). Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 32, 388–407 (2008).

30. Hashimoto, T., Elder, C. M., Okun, M. S., Patrick, S. K. & Vitek, J. L. Stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus changes the firing pattern of pallidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 23, 1916–1923 (2003).

31. Stefani, A. et al. Subthalamic stimulation activates internal pallidus: evidence from cGMP microdialysis in PD patients. Ann. Neurol. 57, 448–452 (2005).

32. Montgomery, E. B. Jr. Effects of GPi stimulation on human thalamic neuronal activity. Clin. Neurophysiol. 117, 2691–2702 (2006).

33. Windels, F. et al. Effects of high frequency stimulation of subthalamic nucleus on extracellular glutamate and GABA in substantia nigra and globus pallidus in the normal rat. Eur. J. Neurosci. 12, 4141–4146 (2000).

34. Perlmutter, J. S. et al. Blood flow responses to deep brain stimulation of thalamus. Neurology 58, 1388–1394 (2002).

35. Lanotte, M. M. et al. Deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus: anatomical, neurophysiological, and outcome correlations with the effects of stimulation. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 72, 53–58 (2002).

36. Vitek, J. L., Hashimoto, T., Peoples, J., DeLong, M. R. & Bakay, R. A. Acute stimulation in the external segment of the globus pallidus improves parkinsonian motor signs. Mov. Disord. 19, 907–915 (2004).

37. Vitek, J. L. et al. Neuronal activity in the basal ganglia in patients with generalized dystonia and hemiballismus. Ann. Neurol. 46, 22–35 (1999).

38. Benabid, A. L., Benazzous, A. & Pollak, P. Mechanisms of deep brain stimulation. Mov. Disord. 17, S73–S74 (2002).

39. Rubin, J. E. & Terman, D. High frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus eliminates pathological thalamic rhythmicity in a computational model. J. Comput. Neurosci. 16, 211–235 (2004).

40. Rizzone, M. et al. Deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in Parkinson’s disease: effects ofvariation in stimulation parameters. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 71, 215–219 (2001).

41. Gale, J. T. Basis of Periodic Activities in the Basal Ganglia–Thalamic–Cortical System of the Rhesus Macaque (Kent State Univ., 2004).

42. Wingeier, B. et al. Intra‑operative STN DBS attenuates the prominent beta rhythm in the STN in Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 197, 244–251 (2006).

43. Kühn, A. A. et al. Increased beta activity in dystonia patients after drug‑induced dopamine deficiency. Exp. Neurol. 214, 140–143 (2008).

44. Bronte‑Stewart, H. et al. The STN beta‑band profile in Parkinson’s disease is stationary and shows prolonged attenuation after deep brain stimulation. Exp. Neurol. 215, 20–28 (2009).

45. Zaidel, A., Spivak, A., Grieb, B., Bergman, H. & Israel, Z. Subthalamic span of beta oscillations predicts deep brain stimulation efficacy for patients with Parkinson’s disease. Brain 133, 2007–2021 (2010).

46. Giannicola, G. et al. The effects of levodopa and ongoing deep brain stimulation on subthalamic beta oscillations in Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 226, 120–127 (2010).

47. Eusebio, A. et al. Deep brain stimulation can suppress pathological synchronisation in parkinsonian patients. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 82, 569–573 (2011).

48. Davidson, C. M., de Paor, A. M. & Lowery, M. M. Application of describing function analysis to a model of deep brain stimulation. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 61, 957–965 (2014).

49. McIntyre, C. C., Chaturvedi, A., Shamir, R. R. & Lempka, S. F. Engineering the next generation of clinical deep brain stimulation technology. Brain Stimul. 8, 21–26 (2015).

50. Quinn, E. J. et al. Beta oscillations in freely moving Parkinson’s subjects are attenuated during deep brain stimulation. Mov. Disord. 30, 1750–1758 (2015).